From the book Remember Goliad (1950), written by William Oberste, the following excerpt describes the events where the Angel of Goliad tries her best to avoid the executions:

“The “Angel of Goliad,” as she is known even to this day, Señora Alavez attempted to prevent the butchery. Not much is known of the identity of Señora Alavez so affectionately remembered in the annals of Texas. From an old newspaper, we have a clipping in which we find a few additional details about her. Writing about the massacre at Goliad, the unknown author tells us in his account, which he grandiosely and incorrectly describes being that “of the only living man who survived it,” the following story of the “Angel of Goliad”:

The courier from Santa Anna arrived at Goliad on the twenty-sixth, having left San Antonio the morning of the same day, distant, one hundred miles. Don F. N. Portilla, the commandant, glanced at the superscription, then at the black seal bearing the president’s arms, an upright arm, and dagger, with the legend “Mano y Clavo,” and sat down on his camp stool to read the missive, uttering something like a groan. Its purport was that he had certain prisoners in charge, that he knew what his duty was, and must execute that duty promptly and rejoin his commander. Portilla threw down the dispatch in disgust. “Duty indeed!” he muttered, leaning his head on the table.

A young woman entered the room, took up the letter, and read it through from beginning to end. Portilla looked up and discovered the intruder with the dispatch in her hand. “I see you have been reading my dispatch ‘ said the commandant. “So—I have. I came here with that very purpose,” she replied. “I suppose you know what it means” “I understand its meaning perfectly. It means the death of every American now in Goliad.” “I have watched for the courier since daybreak and was resolved to know the contents of his dispatch at any peril. What are your intentions?” “To obey the president’s instructions to the letter.” “Promise me that you will do as I wish. Much can be done in a few days. I have friends near the president whom he cannot afford to disoblige; nor can they afford to slight me. Promise me this, and Francisco my husband’s orderly shall start for Bexar tonight. “. . . . They call me Indian, Senora Alavesque; but were I president I would not write that letter for all the lands your father owns; not for all the gold that ever passed the mint of Mexico.”

“The colonel leaned his bronzed Aztec face up on the table, weeping like a child. Doña Panchita Alavesque, a lovely woman of twenty, was the wife of a colonel of the Mexican army, a man of great wealth and power. She had followed him to Texas, partly from whim, but chiefly in the hope of doing good. Her visit that night to the commander saved seventy lives.”

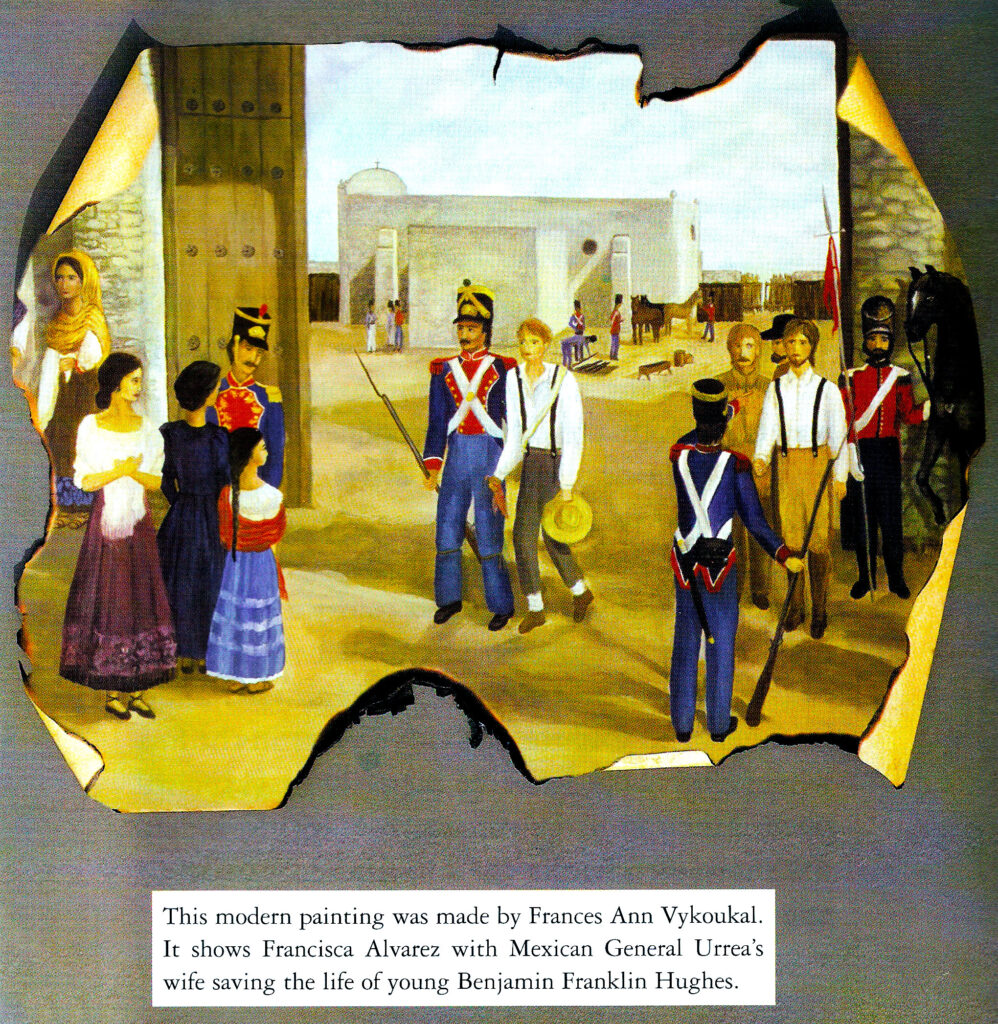

Among those at Goliad who was saved by her intervention was Benjamin Franklin Hughes, Captain Horton’s young orderly, then a lad of fifteen years. [He was born in Jefferson County, Kentucky, September 8, 1820] Hughes, in his old age, wrote an account of his experiences which is preserved among the Philip C. Tucker Papers in the Library of the University of Texas. With slight corrections as to spelling and punctuation, his Goliad reminiscences read:

“The 27th of March, Sunday morning, came and with it an order from the president, General Santa Anna, to shoot us all. We were called out and told to hurry up and get in line to march to a place of embarkation, and we got into line rather hopping and skipping with joy at the thought of soon being home. We were just about starting when I saw quite a number of ladies standing where we had to march by, and two, who afterward proved to be Lady General Urrea and a young lady, Madame Captain Alvarez were evidently ladies of distinction. These, with a little girl ten or eleven years old, was standing in a group with Colonel Holsinger, who seemed to be officiating in the execution of the order for execution.

As we stepped off the young lady spoke to her aunt, the general’s wife, and then the elder spoke to the Colonel, and a Sergeant or corporal came and took me out of the ranks and stood me between the two ladies with the little girl, and the rest marched off. In the space of maybe five minutes, they were halted, and the Mexicans were so arranged as to place our men in a crossfire, and the instant of the halt the order was given to fire. Then I saw for the first time why I was taken from the ranks, and I nudged up to the ladies.

Immediately some of the Mexicans came running back, menacing me with their muskets and bayonets as if they had bayoneted all who were not killed outright. Which they did, and even those who were killed were stuck through with the bayonet rather by way of sport and such was the fate of 332 poor fellows that a few hours before were building high air castles, all to fall suddenly in a few hours with all their plans. Col. Holsinger seemed to be in command, as General Urrea was, it seems, under suspension from duty for not executing the order of General Santa Anna. The Colonel seemed pleased at the ladies taking me in charge and was very kind to me and said he would, and I think he did, do all in his power for me.

The madam wanted me to be one of the family and treated me as a mother, but two or three days passed, and a few companies started on a line of march for Matamoros, and somehow the Colonel had orders to send me to Matamoros, and I was to be taken from the ladies. I was told the understanding was that Madame Urrea was to have me when I got to Matamoros, and Colonel Holsinger made the arrangements for my being well treated, and the ladies and the little girl made me some nice little presents. When the morning came for me to start, I could see tears in their eyes as they kissed me good-bye.”