Lauro Cavazos, Richard Cavazos, Bobby Cavazos

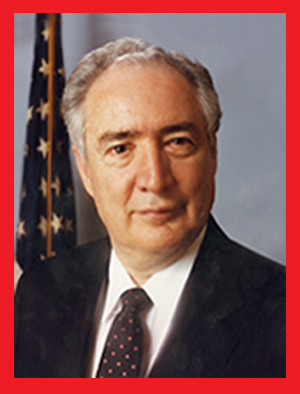

Lauro Cavazos

Lauro F. Cavazos Jr., a former U.S. Secretary of Education who was the first Latino to serve in a presidential Cabinet, has died.

His death at his Massachusetts home Tuesday was confirmed by Texas Tech University, where he served as president from 1980 until 1988. He was 95.

No cause of death was given.

A Democrat whose entire career up to that point had been spent in academia, Cavazos was appointed Education secretary in 1988 late in Ronald Reagan’s second term, a move seen by some as a cynical attempt to boost George H.W. Bush’s presidential aspirations among Hispanic voters, which Reagan denied.

Cavazos was seen as less outspoken and less confrontational than his predecessor, the highly conservative William Bennett.

He vowed to seek better funding for schools, focus federal services on high-risk children, and improve outcomes, especially for Hispanic, Indigenous, and immigrant students. In his two years as education secretary, Cavazos was known for promoting the idea of giving parents the option of deciding where to send their children to school — with limits to prevent segregation — and advocating bilingual education.

He called the dropout rate among Hispanic students “a national tragedy” in September 1989.

Despite attempts to keep out of politics in Washington, he found it difficult.

“I don’t like politics,” he told Texas Tech Today in 2015. “I went there really to try and improve education, and I think we did a pretty good job. I can take pride in the fact that as secretary of education I really focused the federal government on the need to improve the education of minority students and how to do it.”

Cavazos resigned his Cabinet post in December 1990, but according to AP reports at the time, he was fired for failing to make enough progress in reaching the administration’s education goals.

“I am especially proud of the contributions I was able to make in expanding choice in education, promoting the executive order on excellence in education for Hispanic Americans, and raising awareness of the growing diversity of America’s student population,” Cavazos wrote in his resignation letter.

Following his resignation, he came under scrutiny by the Justice Department for allegedly using frequent flier miles earned from official travel to obtain free airline tickets for his wife, who often traveled with him on official business. Federal regulations at the time required employees to turn over travel bonuses to the government. The investigation was eventually dropped.

Cavazos grew up on the King Ranch near Kingsville, Texas, and his family became the first Hispanic family at what had been a segregated school district, according to Texas Tech.

Lauro Cavazos Obituary – Visitation & Funeral Information (deefuneralhome.com)

Encyclopedia.com

Lauro Cavazos (born 1927) was the first Hispanic American to be named to a cabinet position. He served as Secretary of Education under Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush from 1988 to 1990. Educated in zoology and physiology, Cavazos was also a college president and professor who wrote numerous books on medical sciences and medical education. In addition, he consulted internationally on public health issues.

Born on January 4, 1927, on the sprawling King Ranch near Kingsville, Texas, Lauro Fred Cavazos was a sixth–generation Texan with a Mexican ancestry. His father was the cattle foreman of the ranch’s top division, and Cavazos spent his childhood surrounded by ranchers and herders. Cavazos attended public schools in the Kingsville area and then entered the military in the closing months of World War II. He returned after the war and enrolled at Texas Agricultural and Industrial College for a time. He transferred to Texas Tech University (then known as Texas Technological College). He eventually received both his bachelor’s degree in zoology and a master’s degree in zoological cytology from Texas Tech. He then went on to doctoral studies at Iowa State University, where he completed a Ph.D. in physiology in 1954. Cavazos met Peggy Ann Murdock while both were students at Texas Tech. They married and started a family that would grow very large indeed—they eventually had ten children in all. The closeness of their family relationship would later prove a bit problematic when Cavazos entered public service.

In the fall of 1954, Cavazos accepted his first full–time teaching position, at the Medical College of Virginia. For the next ten years he taught anatomy there. In 1964, he moved to Tufts University in Boston, where he taught at the School of Medicine. He also became dean of the medical school at Tufts in 1975. While at Tufts he also sometimes taught classes at Texas Tech and at its Health Science Center.

In 1980, after sixteen years in Boston at Tufts University, Cavazos returned full–time to his alma mater, Texas Tech, accepting a position as university president. He was the first person to lead Texas Tech who had also been an undergraduate at the school. During his tenure as president, he also directed the school’s Health Science Center. While leading Texas Tech, Cavazos was a strong but approachable president with a penchant for compromising among different factions. He cemented a growing reputation for quiet tenacity. In 1984, in a dispute over tenure rules, the Texas Tech faculty approved a no–confidence vote against him; but Cavazos was unfazed and worked behind the scenes for two years to fashion a slightly revised revamping of tenure regulations that was accepted without further protest. He later had a reputation as a teacher’s advocate, but at Texas Tech he did not seem to take sides.

As the leader of a major university, Cavazos soon expanded the reach of his influence. Over the years he published several important books on medical sciences and on medical education. He became a consultant to the World Health Organization and other national and international public health groups. In 1984 President Ronald Reagan gave him an award for Outstanding Leadership in the Field of Education.

In 1988, following the resignation of noted conservative commentator and educator William Bennett as secretary of education, President Ronald Reagan picked Cavazos to succeed him. Cavazos was nominated on August 9, 1988, and confirmed on September 20, becoming the first Hispanic American ever to hold a cabinet post. Because of this achievement, Cavazos received the National Hispanic Leadership Award from the League of United Latin American Citizens.

The appointment of Cavazos came during Reagan’s last months in office, and it was widely viewed as political. Most commentators believed that the prime reason was that having Cavazos in the presidential cabinet would help with Hispanic voters in the presidential campaign of Reagan’s vice–president, George H.W. Bush. But the selection also was sensible on other grounds. Cavazos was well respected as an educator, and Hispanic children had the highest school dropout rate (37 percent) of any racial or ethnic group in the country. “Please, children, don’t leave school,” Cavazos pleaded in Spanish at his first press conference after his confirmation. In addition, Cavazos was a longtime friend of Bush’s, who might have suggested him for the job.

Cavazos’s selection probably came as no surprise to Cavazos, since he had known for eight years that the president was interested in having him on his team. Reagan’s transition team had actually approached Cavazos in 1980, when Reagan was first elected to office, to explore the idea of a cabinet position, but at the time Cavazos had just assumed the presidency of Texas Tech and wanted to stay there for awhile.

When Bush won the 1988 election and took office, he retained Cavazos, not surprisingly; if nothing else, it was one way to fulfill a campaign promise to have a Hispanic member of the cabinet. But it was also a signal of a shift in policy toward more moderation. Cavazos, a Democrat, had a view of the education department that was diametrically opposed to Reagan’s initial impulse to abolish it. Cavazos wanted the federal government to be very active in education and Cavazos’s personal style was very different from the feisty Bennett as well. Cavazos had a well deserved reputation as a quiet consensus builder, and he immediately set to work constructing bridges to Congress that Bennett had burned. Bennett had often attacked teachers and administrators, but Cavazos, by contrast, was from the ranks of these groups and understood and sympathized with their concerns.

Greeting the announcement of Cavazos’s reappointment, Lamar Haynes, the president of the top teachers’ union, the National Educational Association, called it a “hopeful sign that perhaps Mr. Bush will fulfill his campaign promise to become the ‘education President.’ ” Even liberal Democratic Senator Edward Kennedy praised Cavazos, calling him “a man who shares our views about the importance of education.” But conservatives were disenchanted, with the Wall Street Journal, in an editorial, calling Cavazos’s reappointment “the first major blunder” of Bush’s presidency.

Though Cavazos made clear that he agreed with the Republican agenda of more school choice for parents, more accountability for school improvement, and uniform achievement standards, he also said a priority for him would be to make education more accessible to poor children. He spoke in favor of increased federal aid for students and for programs in bilingual education. But he faced the continuing problem of lack of funding for such programs as Bush refused to push for major increases in education allotments. Still, Cavazos hoped to change the direction in which the department had been heading under Bennett. “We’ve heard a lot about budget and trade deficits,” he said. “We’ve got one that’s equally dangerous—the education deficit.”

Cavazos was concerned about strengthening educational opportunities for those students who would not attend college. In a speech on vocational education, he spoke of the “forgotten half” of students who quit school in high school or after graduation from high school and of the increasing problem of functional illiteracy among them. “Our system of education—with federal support—must ensure that non–college–bound students are given the opportunity to acquire the skills they need,” he said.

During his short tenure as secretary of education, Cavazos initiated special programs to fight substance abuse in schools. He advocated stronger parental involvement in education and community–led reforms that would raise standards and expectations among students, teachers, administrators, and parents. But his profile was so low compared to Bennett’s that he was criticized for not rallying public support for legislation that would aid in preventing school dropouts and teacher shortages.

Economist, October 1, 1988.

National Review, March 24, 1989; January 28, 1991.

New Republic, July 10, 1989.

Occupational Outlook Quarterly, Spring, 1991.

Time, August 22, 1988; December 5, 1988; May 29, 1989; December 24, 1990; May 27, 1991.

U.S. News & World Report, May 21, 1990; August 6, 1990.

Richard Cavazos

San Antonio Express-News via AP Lisa Krantz – SAN ANTONIO

As one version of the story goes, a crippling performance evaluation was pushing then-Brig. Gen. Colin L. Powell’s military career toward a dead end when two higher-ranking commanders learned of it.

The two generals were horrified to hear Powell tell them over dinner in 1982 that he planned to leave the Army. One of them was a legendary Texas war hero, Gen. Richard E. Cavazos, who decided to intervene.

It came as no surprise to those who knew Cavazos that he went out of his way to keep Powell in the Army. The first and only Hispanic four-star general, he is now 85, living his last days, his once-encyclopedic mind ravaged by dementia.

It’s painful for those he led and mentored. Some weep when talking of it.

In recent interviews, they described Cavazos as loyal and fearless, a master tactician, an innovator, a charismatic soldier’s soldier. He served as a role model for every Hispanic general who came up through the ranks, retired Army Maj. Gen. Alfredo Valenzuela told the San Antonio Express-News (http://bit.ly/22MH6PY).

In Powell’s autobiography, the man who became the first African-American chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and, later, U.S. secretary of state, called Cavazos an Army legend who saved his career.

The other commander at the dinner table that night, now-retired Lt. Gen. Julius Becton Jr., recalled that Powell had a personality conflict with his supervisor and had suffered for it.

“And what got my attention, and it got Dick’s attention, too, was when Colin said he was probably going to put in his papers,” said Becton, of Fort Belvoir, Virginia, now 89.

Powell confirmed the account through a spokesman.

Cavazos, while he still has a firm handshake, doesn’t talk much. He sat in his wheelchair in a San Antonio nursing home recently and stared gently at his wife, Caroline, as they held hands.

Asked about his father, a World War I veteran who worked on the legendary King Ranch, he replied, “I’m really taken by the building. It appeared out of nowhere.”

There are better days. Caroline Cavazos, 83, is his constant companion, living a short walk away at the Army Residence Community on the Northeast Side. Each night, she helps put him to bed. He’s often anxious, so she climbs into bed and hugs him. In time, he falls asleep.

“He just wants to know that I’m here,” she explained. “We don’t talk much. I hug him. It’s amazing. I’m still in love with him.”

How Cavazos became a Hispanic icon was rooted in his childhood on the King Ranch and forged in Korea, where his fluency in Spanish helped him lead a once-shamed Puerto Rican Army National Guard regiment to combat distinction and where he risked his life to recover men left behind.

“He’s one of these kind of guys in the military, we used to say, ‘He looked good from the top’ — the commanders, his commanders, thought the world of him — and he looked good from the bottom, because every troop thought the world of him,” said Charles Carden, one of his company commanders in Vietnam.

“He was such a good soldier,” added retired Gen. Gordon Sullivan, a former Army chief of staff. “He was born that way. He liked men, he liked combat soldiers. He was courageous, and they knew it, and they knew he couldn’t ask them to do anything that he wouldn’t do with them.”

Richard Edward Cavazos had a theory of leadership that he attributed to the great commanders of history. He called it “moral ascendancy” and said those who possessed it had an edge, an aura of superiority.

Cavazos had it — and it made him the best Army general in a century, said retired Lt. Gen. Marc Cisneros, who was one of Cavazos’ battalion commanders in the 2nd Armored Division at Fort Hood.

“He would talk about Gen. Lee, and that one of the reasons Gen. Lee was superior is because he had moral ascendancy over his Union generals,” said Cisneros, 76, of Corpus Christi. “If the troops had trust and that faith in you, that you were going to lead them well to victory, that’s moral ascendancy.”

Cavazos was the son of a Mexican-American cowhand. His father, Lauro Cavazos, came to Kingsville in 1912, fought as an Army artillery sergeant in World War I and became a foreman of the King Ranch’s Santa Gertrudis division in an era of intense racism.

Being handy with a rope, horses and guns came with the job. Tom Lea’s history of the ranch describes Lauro Cavazos as among the 16 “Kinenos” and guests, including eight Army soldiers, who repulsed an hours-long attack by 58 cross-border raiders at a house in Norias in 1915 during an era of guerrilla violence spun off from the Mexican Revolution.

Lauro and Thomasa Quintanilla Cavazos were determined to give their children a life beyond the ranch and put all five of them through college. Lauro Cavazos Jr. became the U.S. education secretary under President George H.W. Bush.

Dick Cavazos, their second son, got a degree in geology from Texas Tech University, playing football until breaking a leg in his senior year. Studying alongside World War II veterans made an impression.

“He said if you weren’t a serious student after you got a look at them, you were when you did,” Vietnam journalist and author Joe Galloway said. “Those guys had lost five years of their lives, and they were in such a hurry to get it back and get on with their lives that they were total, zero-BS students. And you didn’t want to be sitting in a classroom with them if you were anything less than they were.”

Cavazos served in ROTC before entering the Army. Eventually, he would lead a brigade, a division and an Army corps and finally command all soldiers in the continental United States before retiring in 1984.

But first, he led a company in Korea and a battalion in Vietnam, where he learned that mistakes were as instructive as success.

In Korea, he dressed down a sergeant who shot an enemy soldier who could have been captured. Cavazos then decided to lead the next patrol, and his adrenaline took over when he encountered a North Korean soldier who was carrying pots and pans — a cook, Cisneros said.

“And he said, ‘Guess what I did? I put that mother on full automatic and that was the end of it.’” Cisneros said. “Before you chew somebody out, you have to understand that you could probably be in that same situation.”

Cavazos’ first combat came with the Puerto Rican regiment months after its troops fled their observation post, resulting in the court-martial of more than 90 soldiers. He was awarded a Silver Star, the nation’s third-highest decoration for battlefield gallantry, for leading a small group of men to capture an enemy soldier under fire in February 1953.

That summer, he earned a Distinguished Service Cross for withdrawing his company from Hill 412 amid heavy shelling and rifle fire and going back to look for missing American troops. He found five and “evacuated them, one at a time, to a point on the reverse slope of the hill from which they could be removed,” states the citation for the medal, the second-highest award for valor.

“Lt. Cavazos then made two more trips . searching for casualties and evacuating scattered groups of men who had become confused,” it continued. “Not until he was assured that the hill was cleared did he allow treatment of his own wounds.”

As a colonel in Vietnam, he earned another DSC, in 1967, for organizing a counterattack against a battalion-sized enemy force that hit one of his companies near Loc Ninh.

“When the fighting reached such close quarters that supporting fire could no longer be used, he completely disregarded his own safety and personally led a determined assault on the enemy positions,” the DSC citation said. “The Viet Cong were overrun and fled their trenches.”

Carden, 77, of Biloxi, Mississippi, was then a captain. He observed his boss calmly sitting by a tree and waiting for a round of artillery fire, “absolutely fearless.”

“They brought in napalm,” said Ronnie Campsey, 73, a private first class from Devine who now lives in Long Island, New York. “You could feel the heat from the napalm just taking the breath out of you. That’s how close we were to it. You could see the enemy moving up the hill to get away from the artillery and the air support.”

Cavazos “directed artillery fire on the hilltop, and the insurgents were destroyed as they ran,” the citation states.

Bill Fee, a private first class in Campsey’s company who was badly wounded two days later, said most battalion commanders coordinated ground attacks and search-and-destroy missions by radio from defensive perimeters or from helicopters.

“Cavazos would have none of that. He was on the ground,” said Fee, 68, of Cincinnati. “He fought with us side by side, and he earned our respect.”

Cavazos’ determination to share what he had learned helped shape today’s Army. He was an early supporter of the National Training Center at Fort Irwin, California, a vast desert range used to prepare troops for duty in Iraq and Afghanistan. He was influential in developing the Army’s Battle Command Training Program for higher-ranking officers.

Cavazos would never betray a friend, even if it could hurt his chances of promotion, Becton recalled. And well into his retirement, he was still teaching officers how to fight.

Sullivan, the retired Army chief of staff, said Cavazos had “a real knack for being able to mentor people, very senior people, that was very open, very candid, and guys responded” because of his experience and credibility.

“They would put them in a tent with their radios and make them fight a battle, like they would have to command a battle in the field,” Galloway said. “And it was Cavazos who would go in and lean over their shoulder at the computer and say, ‘You know, son, I think if you do that you’re going to kill that brigade. Is that what you really want to do?”

Cavazos’ real effect was in the hearts of those he led.

“I had the honor of being evaluated by him,” said Valenzuela, who commanded U.S. Army South when it relocated to Joint Base San Antonio-Fort Sam Houston. “When the results were read, I told (him) what he meant to us poor Hispanic kids, growing up in the barrios. . We both cried, not so much on the results, but because of the legacy we both were leaving behind.”

By SIG CHRISTENSON

San Antonio Express-News

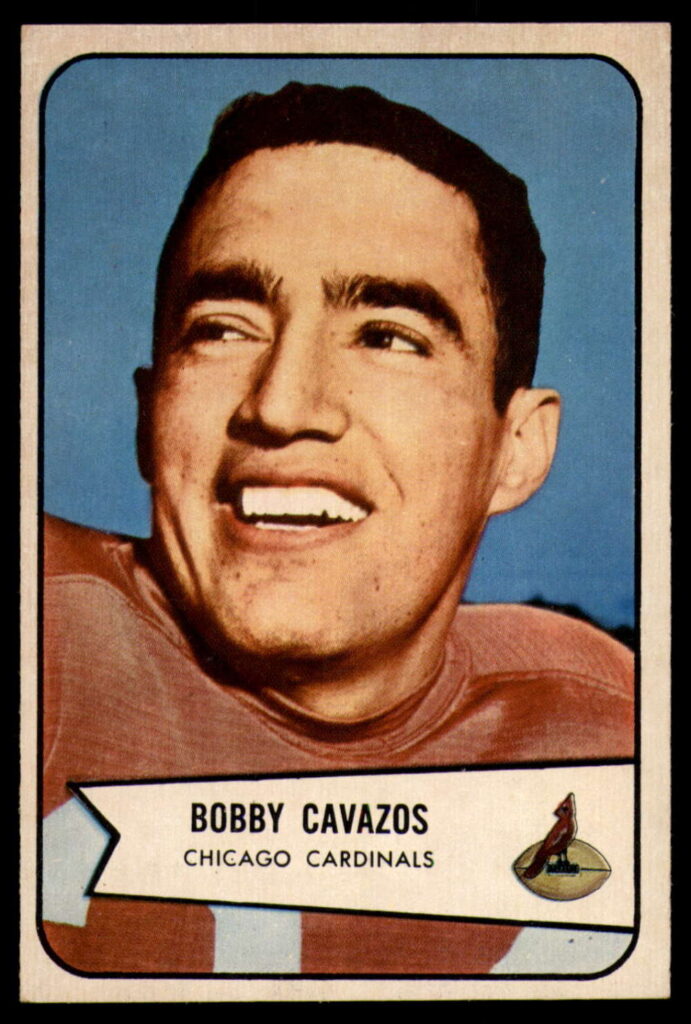

Bobby Cavazos

By Don WilliamsPosted Nov 18, 2013 at 6:45 PM

Bobby Cavazos was one of the most decorated football players in Texas Tech history. By winning 11 games in 1953, Cavazos and his teammates advanced the notion Tech deserved a spot in the prestigious Southwest Conference.

He also was a son of the King Ranch, the famous South Texas spread where his family had roots dating to 1912.

Talking with Cavazos, it could be hard to discern which connection gave him more pride.

“I don’t know. He was proud of both of them,” said Jack Kirkpatrick, Cavazos’ teammate and roommate during the Red Raiders’ landmark 1953 season.

“We made two trips after he got back out of the service and went down to the King Ranch, and he showed us everything they had down there. I tell you what, it was an unbelievable ranch. You couldn’t keep from bragging on it.”

Cavazos, 82, an honorable mention all-America running back in 1951 and a second-team all-American in 1953, died Saturday, according to Tech officials.

Bobby Cavazos was a brother of former Tech President Lauro Cavazos and four-star U.S. Army Gen. Richard Cavazos. Their father, Lauro Sr., was a King Ranch foreman.

“The Cavazos’ family’s name is intertwined in the history of Texas Tech University from Lauro’s leadership, Richard’s service and Bobby’s athletic achievement,” said Tech President Duane Nellis in a statement. “We ask all Red Raiders to join us in remembrance of Bobby Cavazos.”

Cavazos was a senior on the team that went 11-1 and beat Auburn 35-13 in the Gator Bowl. Cavazos was the game’s most valuable player, rushing for 141 yards and three touchdowns. That capped a season in which he finished among the nation’s leaders in points (80) and rushing yards (757).

As a sophomore in 1951, he was honorable mention all-America for a team that beat Pacific in the Sun Bowl for Tech’s first bowl victory. He had 706 yards and nine touchdowns that season and 674 yards and 10 TDs the next.

In each of Cavazos’ last three seasons, he led the Red Raiders in rushing and was named all-Border Conference. A few years later, Tech received a long-awaited invitation into the SWC.

Cavazos was inducted into the Tech Athletic Hall of Fame just 15 years after his senior season. In 1999, he made the Avalanche-Journal list of the South Plains’ top 100 athletes of the century.

“He was just as good as there were,” said Kirkpatrick, a Tech quarterback.

In the 1954 NFL draft, Cavazos was selected 26th overall, the first pick in the third round, by the Chicago Cardinals. But he suffered a shoulder injury in his first preseason game and never played a regular-season NFL game.

Instead, he fulfilled a military commitment and chose to return to the King Ranch.

In a 2009 interview with the Avalanche-Journal, Cavazos said he signed with the Cardinals for $20,000. Before the NFL was a lucrative career choice, he said it was an easy decision to go back home to the family business.

“There was a lot of guys that (football) was the only thing they had going for them,” Cavazos said. “But I knew that I had my job back there with dad on the King Ranch, because I had worked for him every summer.”

Cavazos later became a published author. He wrote, “The Cowboy from the Wild Horse Desert: A Story of the King Ranch” and “The Cowboy from the Wild Horse Desert book two: The Saga Continues.”

Members of the 1953 team say they were particularly close and have remained so over the years, getting together periodically for reunions. The most recent was in October, though Cavazos could not make it.

“Bobby was always one of the topics of conversation, whether he was there or whether he had to miss one because of other commitments,” said Pete Harland, an end on the 1953 and 1954 teams. “He was just outstanding, deserving of every one of the accolades and honors that he ever received.”

In addition to starring on the field, Cavazos in 1953 was named “Mr. Texas Tech University.”

“He was most popular man and all this business,” said Kirkpatrick, a Post resident. “Everybody liked him.”

“Bobby was an awfully, awfully nice guy and very unpretentious about his abilities,” Harland said. “His senior year, it seemed like he came up here a little out of shape because he spent so much time riding horses on that King Ranch. It would take him a few days to get into condition.

“But he was a competitor, a heck of a ballplayer and gave everything he could when on that field.”